Printing as a way of transferring designs on to pottery was first used in Minoan and Mycenaean societies using natural sponges to create shapes and mottled effects in liquid slip. Clay, wood and other natural materials were also used to print and impress decorative designs onto the clay surface.

Transfer printing on to ceramic surfaces developed in line with industrial techniques for printing on paper. In the 18th Century engravings and etchings on copper plates began to be used to make transferred designs on to ceramics. Linseed oil was wiped into the lines of the engraved plate, the surface of the plate wiped clean and a gelatine glue sheet, known as a ‘bat’ pressed into the oiled lines. The gelatine ‘Bat’ was used to transfer the image on to the already fired and glazed ceramic surface. This was then dusted with powdered ceramic colour, which would stick only to the transferred image, and fired again.

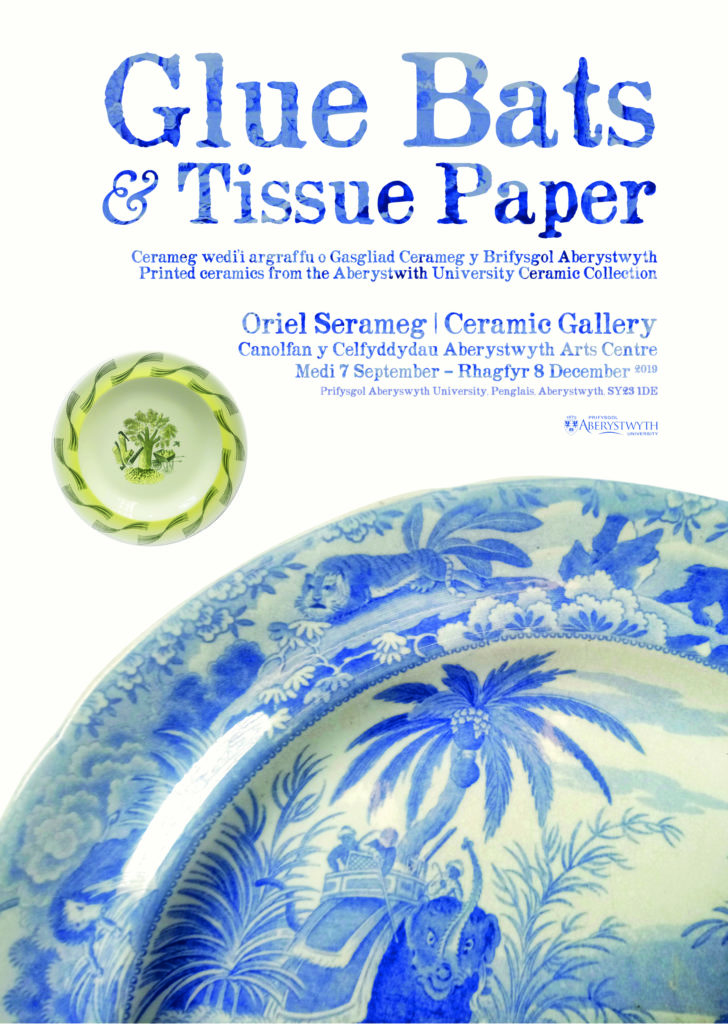

Later, the process was refined using paper transfers and the development of ceramic inks, particularly cobalt blue. Blue and white china flourished in the 19th century and designs imitating ‘Old Master’ paintings or Chinese ceramics were produced by the many potteries particularly in Stoke-on–Trent. This led to a ‘Chinamania’ craze for such wares in the 19th century described by Lady Charlotte Guest, a noted collector, as ’a ridiculous rage’.

In this exhibition artists Paul Scott and Philip Eglin manipulate the designs and imagery of 18th and 19th Century blue and white china and use the industrial past of British ceramics (the Spode factory ware in particular) as a feature of their work.

Multi-coloured printing on ceramics in the UK developed in the 1840s; illustrations including satirical political cartoons were printed on to jugs, cups and plates. Souvenir ware was also mass produced to be sold in seaside towns and at popular Victorian tourist spots.

Lowri Davies makes affectionate references to Welsh imagery used on souvenir ware as well as china displays on Welsh dressers. She transfers her drawings on to slip cast tableware using decals. Maria Gezler uses screenprinting techniques to transfer her child’s drawings on to folded porcelain.

Factories such as Wedgwood commissioned artists such as Eric Ravilious to create designs. Ravilious worked for the company from 1936 until 1940 and created commemorative ware as well as tea services including Afternoon Tea (1937), Travel (1938) and Garden Implements (1939). Later in the 20th Century Glenys Barton and Vicky Shaw also worked for Wedgwood using photo–lithography and screenprinted designs.

By the end of the 19th Century, photographs could be reproduced on ceramic surfaces using lithography and this was particularly popular for reproducing portraits on ceramic plaques for gravestones. Printing with photographic decals became popular in contemporary ceramic works in the 1960s and 1970s when ceramicists began to use them as over–glaze designs. Helga Gamboa, Stephen Dixon and Conrad Atkinson use published newspaper photographs in their work to make political comments.

Ceramicists today continue to explore the relationship with ceramics and print and embrace the possibilities of digital printing. Jonathan Keep uses a 3-D printer to create sculptural forms which could not be made by the human hand. Ingrid Murphy collaborates with others on digital fabrication technologies to create interactive ceramic works. New technologies no doubt will continue to influence future methods of printing on clay, but for the present at least, they are combined with traditional making skills.

Jonathan Keep International Ceramics Festival 2013

Glue Bats and Tissue Paper Powerpoint